Love the Landscape

By Dan Shaver

The woods are a little less noisy this time of year. The cold grip of winter is close at hand and the songbirds that flood into the Brown County Hills in the spring have defended territories, attracted mates, built nests and hopefully fledged their young and headed south for the winter. Many of these birds return to the western slopes of the Andes Mountains in South America where they face grave threats to their mountain habitat from fragmentation and conversion of land to non-forest uses. But their time in the Brown County Hills helps them prepare.

So think ahead to next spring. Songbirds, like the Cerulean Warbler (Figure 1), will start an incredible journey from the Western slope of the Andes Mountains. They make their way through Central America and then launch themselves from the Yucatan peninsula to make an 18-24 hour non-stop flight over the Gulf of Mexico. The Cerulean Warbler, weights about as much as a AAA battery and can lose up to 1/3 of its body weight just making the flight over the Gulf. But that is not the end of the journey. The birds then make their way up through the southern United States feeding and foraging as they go. They take some time, resting occasionally to fuel up, but looking for something more. What they are looking for is a large block of contiguous forest, abundant food resources and nesting sites that will ensure the survival of their young. What they are looking for is the Brown County Hills.

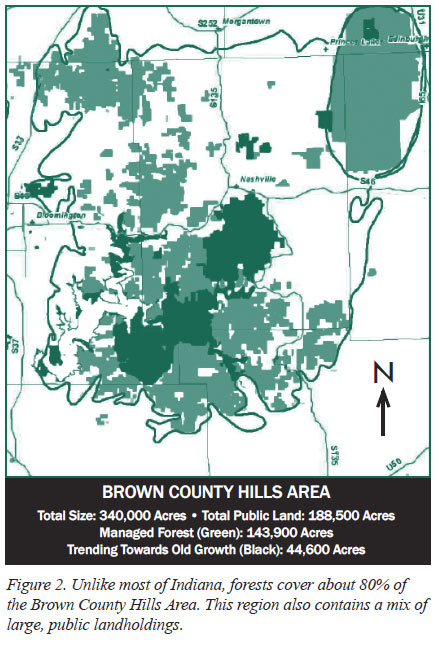

Although size matters to these birds, just a big forest will not ensure their survival or viability over time. The quality, composition (tree species and community types), and the structure of the forest make the difference. There is also the reality that what is good for one bird species, may not be good for another bird. Of the birds that like big forests, there are some like the Cerulean that like to live high in the top of the trees, Ovenbirds like to nest on the forest floor, Yellow-breasted chats like young forest and the Louisiana Waterthrush likes forested streams with overhanging banks. The forests of the Brown County Hills provide all of these habitats and more (Figure 2). Yet, it is always changing. Young forest becomes old, old forest begin anew, tornados reset the forest, ice storms disrupt the canopy and fire alters and adjusts the understory. For thousands of years these disturbances naturally adjusted the forest to provide the various habitats needed. Species moved and adjusted to follow the habitat they wanted. This was when forest covered 80% of Indiana. Now forest covers only 20% of Indiana, but in the Brown County Hills forests still make up 80% of the landscape. Unfortunately the influence of natural factors has been disrupted. We suppress fire, the odds of a tornado disrupting forest land in Indiana has been changed, we have added an overabundance of deer that alter the understory of the forest and we have introduced invasive plant species that alter the composition and structure of the forest.

So we have less forest that has to provide many habitats to many species. The reality is not every acre can provide all habitat to all species. Fortunately we have a wonderful mix of public land in the Brown County Hills. We have the Hoosier National Forest and the Deam Wilderness Area, we have Yellowwood and Morgan-Monroe State Forest, we have Brown County State Park, we have Lake Monroe and Reservoir land, we have Camp Atterbury and we have a scattering of IDNR Nature Preserves, land trust properties, and county and local parks. We also have a lot of private land that is a mix of forest age classes, but subject to subdivision, conversion and inappropriate forest management. The forest diversity found on both the public and private land is very beneficial to migratory songbirds and many other species. The public lands are not all managed the same, and this is good and somewhat intended by having the Indiana Department of Natural Resources (IDNR) split up into different Divisions with different missions. It is all state land, but some is managed for timber, some recreation, some wildlife and some natural area conservation. As the IDNR evolved they realized not every acre could provide everything to all citizens. Just like every acre cannot provide everything to all bird species. The Hoosier National Forest is all one property, but managed for multiple-use having different areas managed for different objectives (See Hoosier National Forest Page 14). If all the public land in the Brown County Hills was managed like the Deam Wilderness Area or Brown County State Park, biodiversity of plants and animals would suffer. If all the public lands were managed like Morgan-Monroe and Yellowwood State Forest there could be problems too. Each of these various public lands provide landscape benefits to migratory songbirds and other species. We need and want some areas to be allowed to grow and mature into deep, high canopy forest. We need and want some areas to be managed for a more open oak woodland condition. We need and want some areas to be managed for young forest, teenage forest and old forest. Every acre of forest cannot provide everything for every species. Just like each acre cannot provide everything for every person. The birds seek out and utilize the land that provides the habitat they need. Like the birds, people should seek out and use the public land that meets their needs for solitude, biking, hunting or hiking. If we just have old trees, we lose everything associated with the young forest. We need diversity within the forest. Cerulean warblers don’t want to nest in young forest. They find a mature forest to nest in and then utilize young forests to raise their young. People that don’t want to hike in an area that shows evidence of timber harvesting, can hike in the Deam Wilderness area, or Brown County State Park. Hunters that want habitat diversity can seek out the state forests or wildlife areas instead of parks or wilderness areas.

Diversity of tree age classes, tree species and habitat replication across the landscape of the Brown County Hills is beneficial for neotropical migratory songbirds. The disturbance to the forest whether it is natural like tornados, ice storms or fire or manmade like timber harvesting is critical in maintaining forest diversity and in turn diversity of songbirds. Every year when the songbirds fly south, they head back into peril. They don’t know what they will find when they return south and can’t do anything about it. There is no guarantee that the habitat they need will be there when they arrive. So in the Brown County Hills, we can help. If we maintain the structural and age diversity within the forest of the Brown County Hills, the better the habitat will be reflected in more nesting success and more birds fledging and thriving. The more birds we can send south in the winter, the more that have a chance to survive and return in the spring to start the cycle over again. The birds are compelled to migrate. They fly into peril on their wintering grounds. The least we can do is guarantee that when they make that perilous journey across the Gulf of Mexico in the spring that they return to the guaranteed diverse, rich and resilient forests of the Brown County Hills.

Although this article focuses on the Brown County Hills area, all private and public forest land across the state are important for the long term health and sustainability of plant and animal populations. We have many bird species that migrate through Indiana headed north to the vast boreal forest, but the small woodlots and riparian forests across Indiana are temporary stopover habitat for species to rest and refuel before heading further north or south depending on the season. So whether you manage your land for wildlife, timber production, hiking, old forest or a combination of them all, your forest is important to the landscape we love and call home.

Dan Shaver is the current president of the Woodland Steward Institute. He is also a professional forester and director of the Brown County Hills Project with the Nature Conservancy in Indiana. The BCHP is a community-based program working to help ensure the viability and health of the forests.