The Birders’ Dozen Profile 2: American Woodcock

Welcome to the second iteration of the Birders’ Dozen series from Forestry for the Birds. The Birders’ Dozen are forest birds that can benefit from targeted management practices, as most are declining due to habitat loss. We’ve curated this list to cover a wide range of habitat types, from young to mature forest, open to closed canopy, or dense to non-existent shrub layers. Our goal is to engage landowners and foresters in the process of managing forests for wildlife, or “forests for the birds.”

In this second profile, we’ll meet the American Woodcock, a funny-looking shorebird that prefers to spend its time in old fields and young forests rather than the beach. This bird is popular amongst birders and hunters alike, even inspiring the name of a popular sporting dog breed, the Cocker Spaniel. The woodcock is one of our earliest breeders, one of the reasons we’re introducing it now – it may be winter, but spring is coming sooner than we think!

Its peent call ringing at dawn and dusk to signal early spring, the American Woodcock is a beloved and unique species. Though it is classified as a shorebird, the woodcock spends most of its time in brushy young forests foraging for earthworms. It is popular as a game species, but is currently threatened by habitat loss and in need of targeted management to preserve its preferred nesting habitat.

Natural History

Unlike most shorebirds such as the Killdeer or Bar-tailed Godwit (the world record holder for longest non-stop bird flight during migration), the American Woodcock does not spend its days wandering up and down rocky beaches or gravel roads looking for tiny invertebrates. Instead, it peruses leaf litter in young forests, eagerly watching and probing for earthworms. Its eyes, uniquely situated on the back of its head, allow it to watch for predators while nose-deep in leaves and dirt.

Unlike most shorebirds such as the Killdeer or Bar-tailed Godwit (the world record holder for longest non-stop bird flight during migration), the American Woodcock does not spend its days wandering up and down rocky beaches or gravel roads looking for tiny invertebrates. Instead, it peruses leaf litter in young forests, eagerly watching and probing for earthworms. Its eyes, uniquely situated on the back of its head, allow it to watch for predators while nose-deep in leaves and dirt.

One of the woodcock’s most distinctive behaviors is its elaborate “sky dance” courtship display at dawn and dusk in early spring. In March and April, woodcocks return from their wintering range in the southern portions of North America and begin to defend breeding territories in old fields and forest openings. In order to attract a mate, male woodcock select a singing ground that’s an average of 750 square feet, usually a clearing or old field within a young forest landscape. Aldo Leopold famously wrote about the woodcock’s sky dance in his A Sand County Almanac (1949), describing him as a romantic performer in an amphitheater of forest, carefully choosing a time of day with light like candles. “Knowing the place and the hour, you seat yourself under a bush to the east of the dance floor and wait, watching against the sunset for the woodcock’s arrival. He flies in low from some neighboring thicket, alights on the bare moss, and at once begins the overture: a series of queer throaty peents spaced about two seconds apart,” Leopold writes.

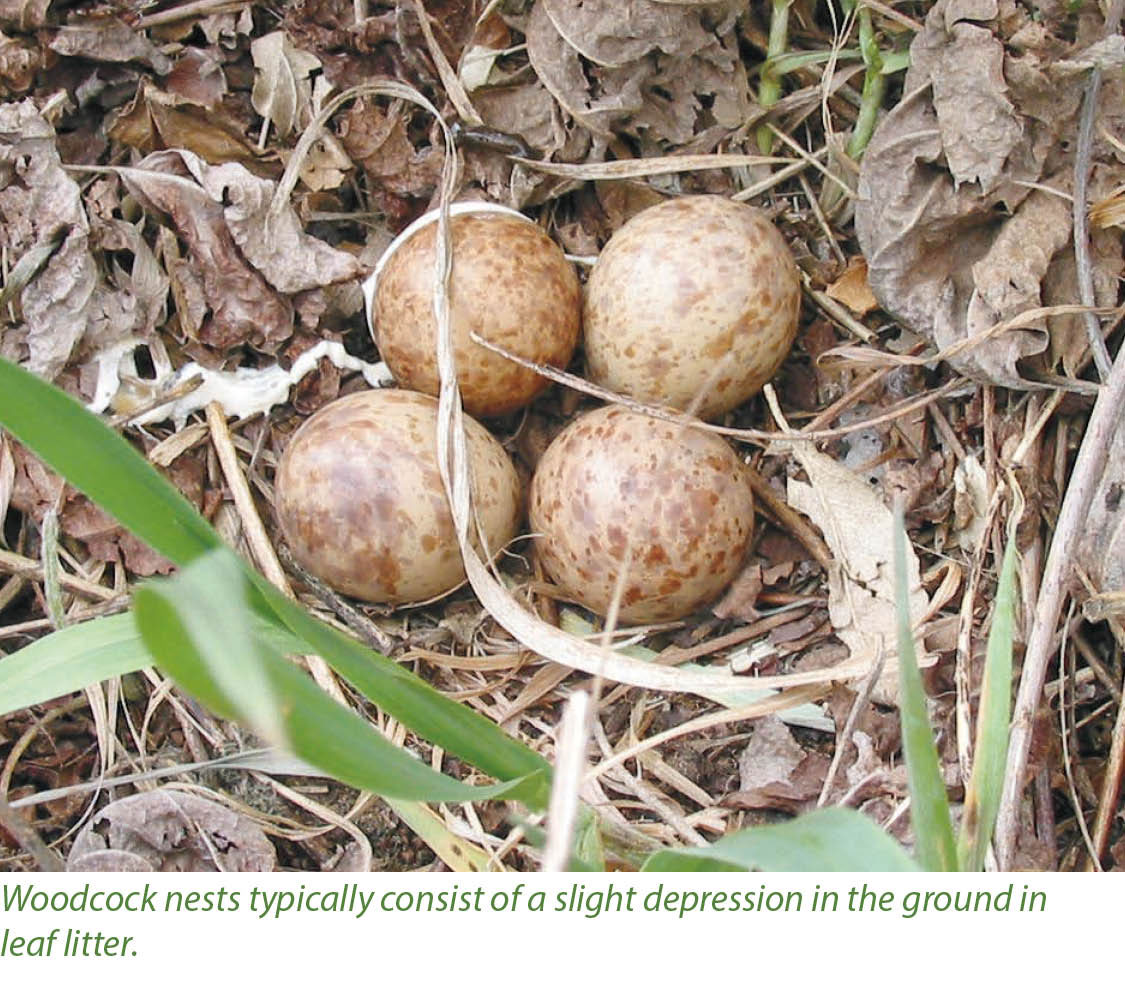

As the dance begins, the male stops his peent calls and spirals upwards, wings twittering, often up to three hundred feet high. Once he has reached his peak, he silently plummets to the earth before again landing in his amphitheater. Males and females, once this courtship display has proven successful, nest in shallow depressions of leaf and twig litter in young forest. These sites often have high densities of shrubs and saplings, which can provide shelter from predators.

Females, which are the sole caregivers, will lay clutches of 1-5 small mottled brown, gray, and orange eggs. Females incubate these eggs for approximately three weeks before they hatch into precocial young, which are able to leave the nest within a few hours of hatching and are fully grown and able to fly within a month. By late October or November, coinciding with hunting seasons, migrating woodcocks have begun leaving their summer sites and are en route to their wintering locations.

Habitat Management

Management plans for American Woodcock often recommend creation of young forests with dense midstories for shelter and little ground cover, which benefits earthworms. Young forests, common throughout much of the 18th and 19th centuries, have now aged in many areas. This natural succession process, while benefitting mature forest specialists, has reduced the amount of habitat in which American Woodcock can find their preferred food and breeding areas.

Hunting, since harvest rates have declined since the 1970s, likely does not impact woodcock populations. Instead, habitat loss, specifically of young forest in the Midwest, has been named as the likely culprit for regional population declines. Even-aged management that creates clearings near young forest can greatly benefit the woodcock and other early successional species. The American Woodcock Conservation Plan (Kelley et al. 2008) recommends even-aged management techniques on short rotation cycles to create habitat for these charismatic birds.

Conclusion

Despite population losses due to lack of suitable habitat, the American Woodcock can greatly benefit from the actions of woodland owners in Indiana. Private land management targeting creation of clearings and young forest can foster areas in which males can display and females can raise young. Projects such as Forestry for the Birds are geared towards private landowners and foresters, with the goal of benefitting both forest health and American Woodcocks.

Special thanks to the Alcoa Foundation, the Indiana Forestry Educational Foundation, and The Nature Conservancy for their support and leadership of Forestry for the Birds.

References

Brenner, Stephen J., Bill Buffum, Brian C. Tefft, and Scott R. McWilliams. 2019. “Landscape Context Matters When American Woodcock Select Singing Grounds: Results from a Reciprocal Transplant Experiment.” The Condor 121 (1). https://doi.org/10.1093/condor/duy005.

Dessecker, D.R., and D.G. McAuley. 2001. “Importance of Early Successional Habitat to Ruffed Grouse and American Woodcock.” Wildlife Society Bulletin.

Kelley Jr, J.R., Williamson, S. and Cooper, T.R., 2008. American Woodcock Conservation Plan: a summary of and recommendations for woodcock conservation in North America.

Leopold, Aldo. 1949. A Sand County Almanac. Oxford University Press, Inc.

McAuley, Daniel G., Daniel M. Keppie, and R. Montague Whiting Jr. 2020. “American Woodcock (Scolopax Minor).” Birds of the World, March. https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/amewoo/cur/introduction.

Jessica Outcalt is an independent consultant working with The Nature Conservancy since 2020. Her “day job” is as a field technician doing avian surveys with WEST, an environmental consulting firm. She completed her BS in biology at Taylor University, her PhD in wildlife ecology at Purdue University, and is passionate about birds and getting people involved in conservation and scientific processes.